“If you can make it to the new year, this is our best option.”

In the first quarter of 2017, the FDA approved Matrix-Induced Autologous Chondrocyte Implantation (MACI) for use on articular cartilage defects of the knee joint in the US. Insurance companies, as usual, lagged behind for coverage of all defects.

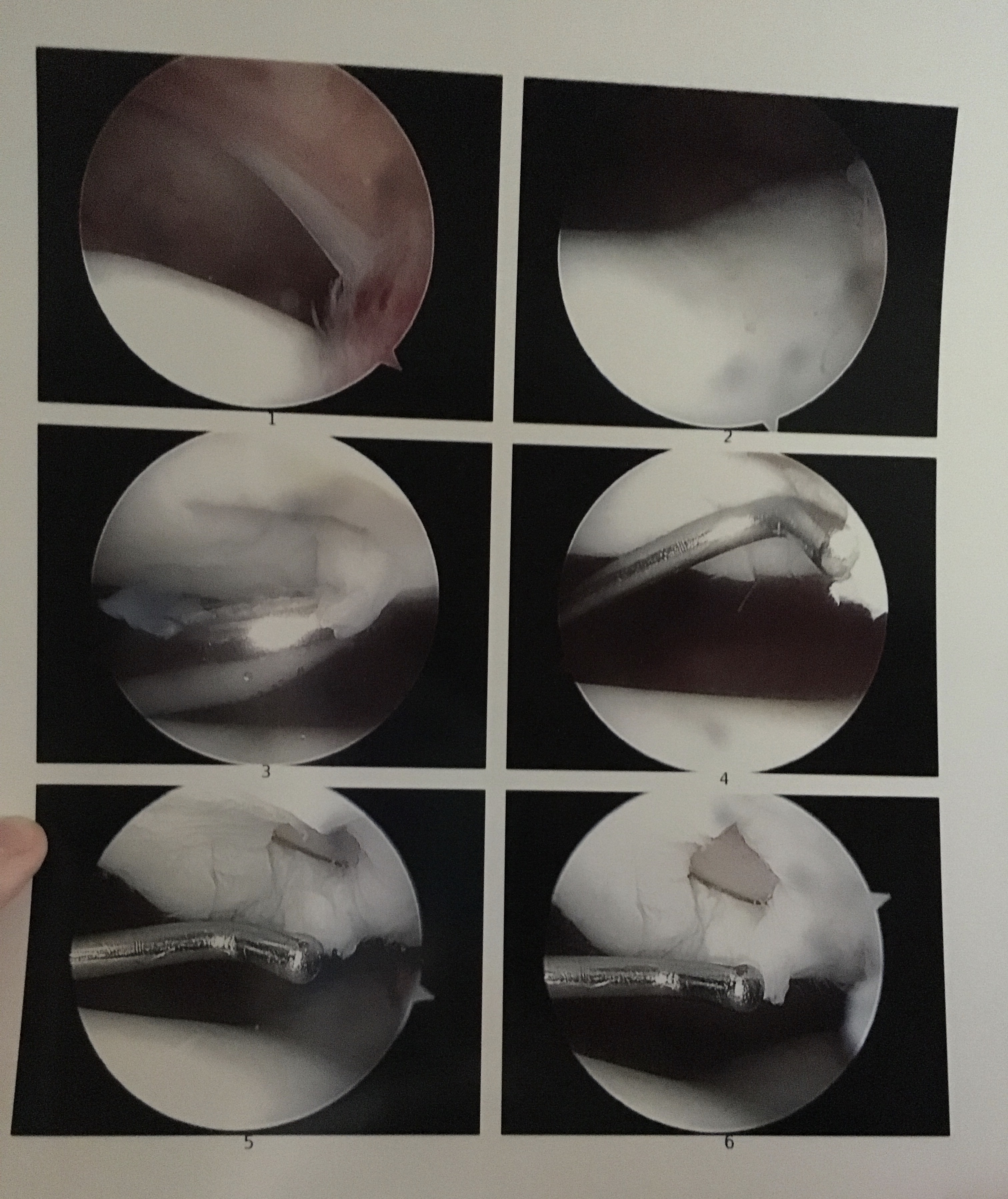

MACI replaced the ACI procedure that had been in use for quite a few years. The greatest difference between these two procedures is that MACI utilizes a man-engineered matrix to load healthy cells into your defect, whereas ACI mostly utilizes your own tibial periosteum to hold the healthy cells. Both procedures require an initial surgery to take a biopsy of healthy tissue that can be used to develop these cells which can mature anywhere from 12-18 months. Both procedures are also frequently coupled with an osteotomy or anteromedialization.

The goal of the MACI or ACI surgery coupled with an osteotomy of the tibial tubercle is to move the weight bearing surface of the joint away from the defect. Almost like a semi-safety net that should allow for a decrease in pain and other symptoms just in case the graft ends up failing.

None of this was explained to me. As I peppered my doctor with a multitude of questions on what procedure would result in the best outcome for my specific defect area, he insisted that the revolutionary aspect of MACI was my best option with the highest chance of success.

While beginning my research, I believed an 85% success rate was good enough for me, but I had tunnel vision. Everything leading up to hearing about MACI has been the worst case scenario that was presented. I didn’t consider many of the things that could go wrong committing to a procedure that was just brought overseas.

And so I left 2016, and the 16th year of my life looking forward to the next year. It would only take two surgeries, and a solution was in sight. It wasn’t experimental, it was medicine. Little did I know.